Anatomy of a Failed Moral Panic

A Diagnostic—with a Pulse

Anatomy of a Failed Moral Panic

A Diagnostic—with a Pulse

By Jim Reynolds | www.reynolds.com

Put simply, a moral panic is a socially amplified wave of fear and indignation in which a person, group, or behavior is rapidly cast as a grave moral threat, prompting demands for urgent collective action that are disproportionate to the actual evidence.

Moral panics are not spontaneous. They are assembled.

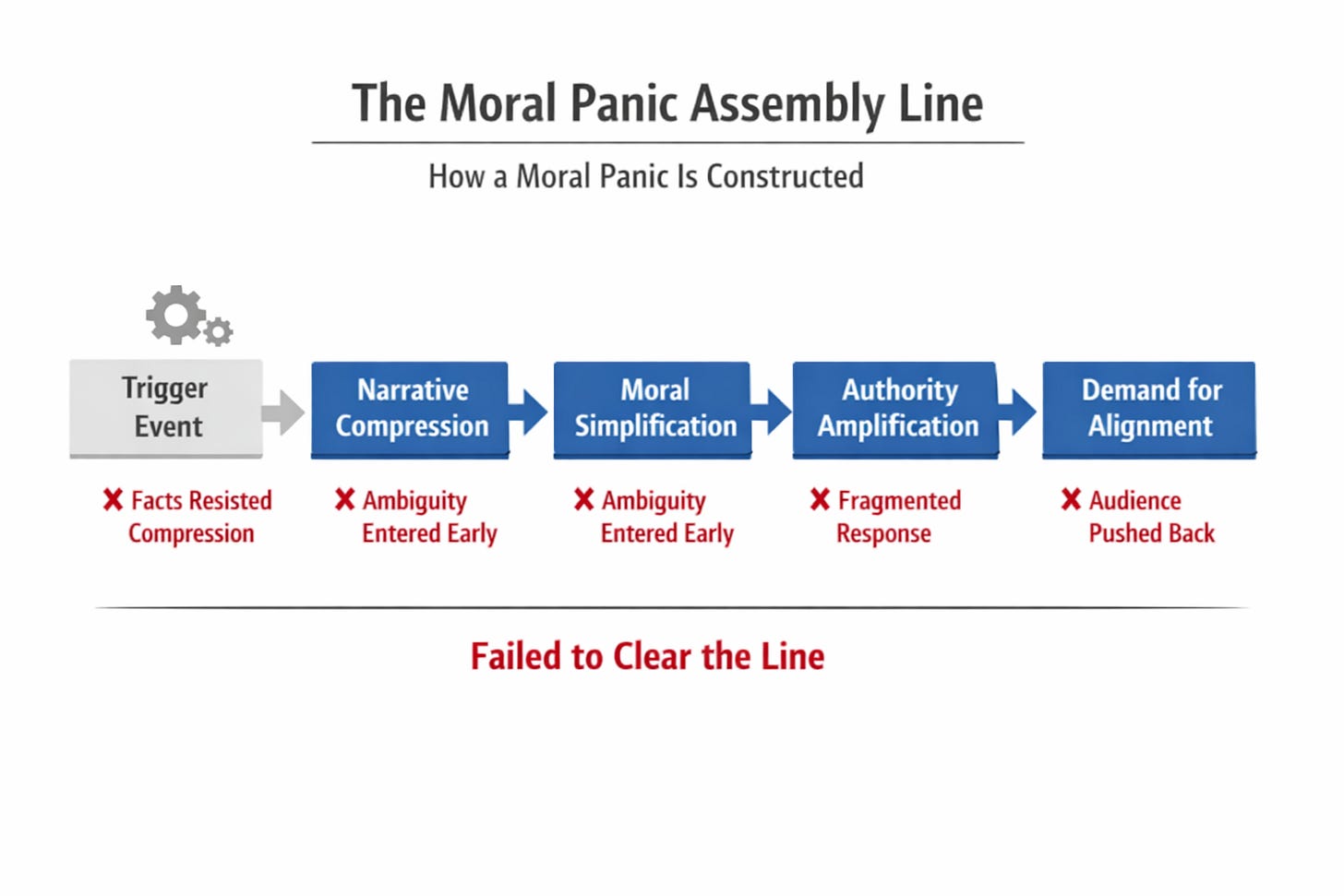

They follow a familiar pattern: a triggering incident, rapid narrative compression, moral simplification, amplification by authority figures, and finally a demand—explicit or implicit—for collective emotional alignment. When successful, they move faster than facts and leave little room for dissent. When they fail, the failure is revealing.

The recent attempt to ignite a national moral panic over the shooting of Renee Nicole Good in Minneapolis is a case study in why the old formula no longer works as reliably as it once did.

The Panic Template

On paper, this episode had all the necessary ingredients. A civilian death involving federal law enforcement. A sympathetic personal profile. A city with unresolved historical trauma. Familiar rhetorical cues—unarmed, peaceful, community, justice—were deployed almost immediately. Political leaders issued forceful condemnations. Media outlets hinted that another national reckoning might be imminent.

In earlier years, that would have been enough.

This time, it wasn’t.

Where the Panic Stalled

The failure was not primarily ideological. It was structural.

First, the facts resisted compression. Video evidence appeared quickly, from multiple angles, complicating the clean victim-villain binary on which moral panics depend. Ambiguity entered early—and ambiguity is fatal to mass outrage.

Second, the authority chorus fractured. Instead of a unified escalation, responses diverged. Some officials urged restraint. Others rushed to indict. The lack of synchronization weakened the signal and exposed internal disagreement that is usually hidden until after the moment has passed.

Third, the audience has changed. The public no longer consumes these events passively. People now expect to see primary material—video, timelines, competing analyses—before surrendering judgment. The trust gap that once allowed narratives to sprint ahead of evidence has narrowed.

Finally, and most decisively, the panic no longer aligned with lived incentives. After years of rhetorical escalation followed by institutional paralysis, many people have learned that moral panic often substitutes for resolution. It promises catharsis, not outcomes. That recognition dampens enthusiasm.

Outrage fatigue is real—not because people don’t care, but because they’ve seen how often care is harvested and discarded.

A Shift in the Ecology

What we are witnessing is not the disappearance of moral panics, but a shift in their ecology.

They still form. They still attempt to mobilize. But they now compete with:

• instant documentation

• decentralized interpretation

• exhaustion from prior overreach

• and a growing suspicion that outrage has become a governing tool rather than a moral response

In this case, the attempt to frame the incident as another definitive moral rupture failed because too many people recognized the scaffolding. The cues were familiar. The emotional demands felt rehearsed. The mismatch between rhetoric and reality was visible in real time.

The Necessary Polemic

There is an uncomfortable irony here.

The same political and media actors who insist that the public must trust the process are often the first to abandon process in favor of narrative urgency. When that urgency fails to land, the response is not reflection but irritation—directed at a public that no longer reacts on command.

That irritation is the tell.

It reveals an expectation of compliance that no longer exists. Moral authority is assumed, not earned. Emotional alignment is demanded, not persuaded. And when the spell fails, the public is blamed for being cynical rather than credited for being discerning.

Diagnostic Conclusion

Moral panics succeed when they outrun scrutiny. This one didn’t.

It stalled because the environment has changed: information moves faster, trust moves slower, and narratives now have to earn assent rather than assume it.

Outrage isn’t gone. It’s just harder to manufacture.

For those who relied on panic as a political accelerant, that may be the most destabilizing outcome of all.

——————

Addendum: Why This Wasn’t George Floyd

Seen through this same diagnostic lens, the George Floyd episode shows what a fully successful moral panic required in 2020 and why the same machinery now misfires.

The comparison is unavoidable—and instructive.

The George Floyd killing ignited a successful moral panic because it arrived in a radically different informational and psychological environment. Video appeared early, but context arrived late. Institutional authority aligned almost instantly. Media, corporate, political, and cultural actors moved in lockstep. Dissent was actively suppressed. The public was isolated, anxious, and primed by lockdowns and uncertainty.

In short, the panic faced little resistance.

By contrast, the Minneapolis shooting of Renee Good occurred in a world shaped by the aftereffects of that moment. The public now expects to see everything, immediately. Competing interpretations appear within hours. Institutional voices fracture instead of harmonize. And many people have learned—sometimes the hard way—that moral panic often produces spectacle rather than solutions.

The difference is not compassion. It is cognition.

People did not become colder. They became more careful.

And once a population learns to slow the emotional reflex that panic requires, the machinery that depends on it begins to stall.

That, more than any single fact of this case, explains why this moral panic failed—and why future attempts will find the ground less fertile than it once was.

—————

Author’s Note

One thing I’ve noticed over the past few years is that these moments don’t land the way they once did. That’s not because people care less, but because they’ve learned to see more. With access to primary evidence, competing interpretations, and pattern-based analysis, readers are less dependent on a single narrative voice to tell them what happened—or what to think about it.

Once you’ve developed that kind of vision, it tends to stick.

I don’t think so. The left would have said: He should have gotten out of the way. That’s about it. If actions (and reality) do not serve the narrative then they are steeply discounted.

What if the results of this encounter were reversed?

He fired and missed and she hit him with her car and killed him.

Would the same degree of moral panic occurred?