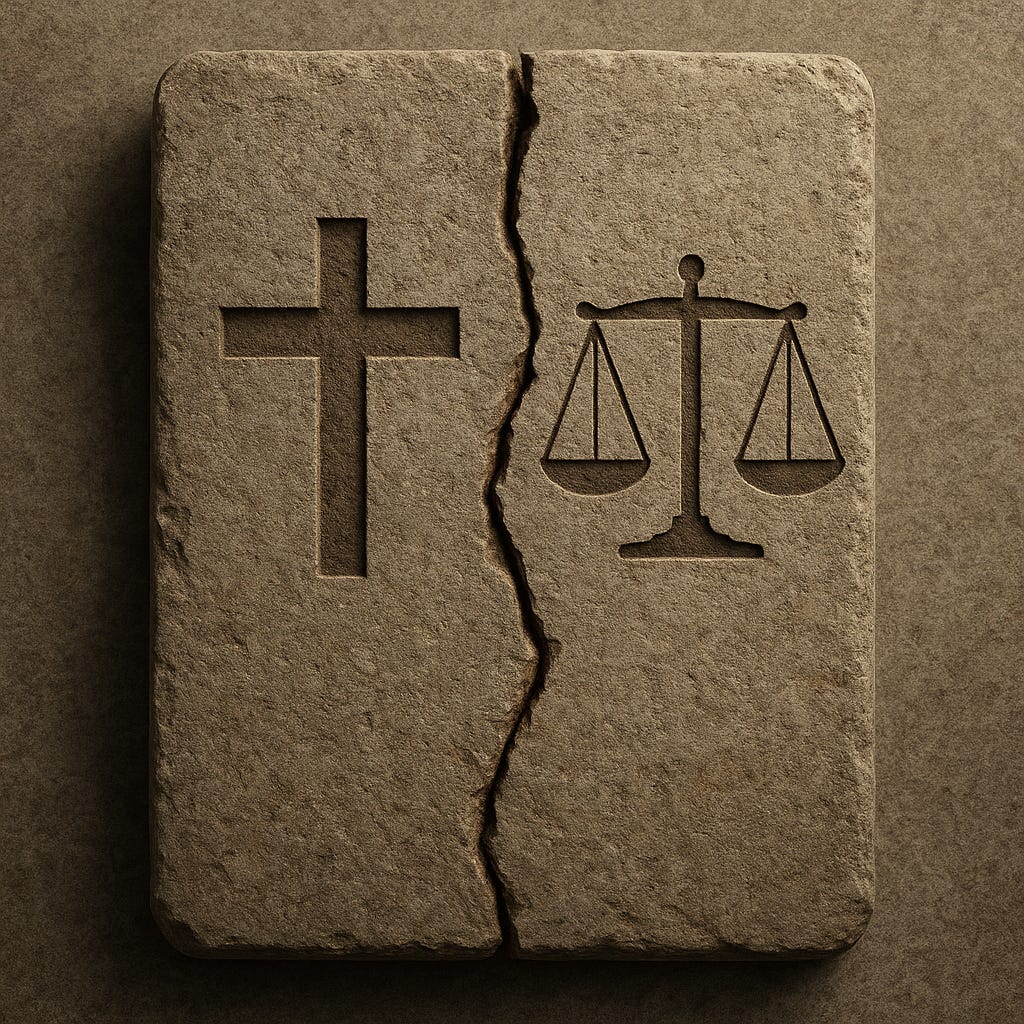

Forgiveness and Its Limits

Why We Love Our Enemies—And Why We Don’t Always Let Them Go

Author’s Note:

At first, this subject felt almost impossible to tackle — too much history, too much theology, too much weight. But piece by piece it came together. Longer than my usual essays, yes — yet the extra space was necessary to honor the history and give the argument the weight it deserves. Some topics demand more than a quick strike; they demand the long arc of context.

Forgiveness and Its Limits: Why We Love Our Enemies—And Why We Don’t Always Let Them Go

By Jim Reynolds | www.reynolds.com

Forgiveness and Justice

Forgive, so hatred doesn’t last—

but punish, so the crime stays past.

Mercy lifts the human heart,

while justice keeps the world from falling apart.

Introduction

“Love your enemies.” “Forgive those who wrong you.” Few phrases are more universally recognized—or more universally resisted. They cut against instinct, against human pride, and against the hard-earned lessons of politics. They are also phrases that echo across two thousand years of Christian tradition and beyond, shaping cultures and controversies alike.

The difficulty is not in hearing the words but in applying them. How do we reconcile the call to forgive with the demand for justice? When does forgiveness become enabling? And what is the reason—beyond “because the Bible says so”—that forgiveness has been lifted up as a moral virtue?

These questions matter now as much as they did in the first century. In personal life, forgiveness can heal wounds. In public life, indiscriminate forgiveness can destroy a society by rewarding wrongdoers. The real challenge is to understand both sides of the argument, see how thinkers have grappled with it through the centuries, and arrive at a synthesis that makes sense for our world.

I. Historical and Scriptural Context

To understand the original call to forgive, we must remember the setting. Christianity did not begin as the faith of empires, but as a tiny, powerless sect living under Rome. Jesus and his followers had no political leverage, no army, no institutions to protect them. They faced the overwhelming force of an empire that crushed dissent with cruelty.

In that context, retaliation was not only impractical—it was suicidal. An ethic of forgiveness was not simply lofty; it was survival. To “turn the other cheek” was to refuse the endless cycle of vendetta that could obliterate a fragile community before it even took root. It also marked a radical departure from the honor-revenge culture of the time.

Two thousand years later, the situation is profoundly different. Christianity is no longer a powerless sect. In much of the West, Christians and their institutions have real strength, legal protections, and social capital. The posture of defenseless martyrdom is no longer inevitable. And that means the question of forgiveness can no longer be understood only as it was then; it must be reconsidered in light of a new reality.

Turning the other cheek made sense when Rome had the sword. Today, pretending we’re powerless is just play-acting.

Forgiveness is noble; forgetting is suicidal.

II. Theological and Philosophical Roots

Augustine argued that hatred enslaves the hater. To love one’s enemy is to will their good, which might include their moral change. But he also defended the idea that public justice is compatible with private forgiveness. One may forgive an enemy’s soul while still supporting punishment for the sake of the community.

Aquinas sharpened the distinction: interior charity requires forgiveness, but exterior justice requires proportionate penalties. For him, loving an enemy did not mean sparing them consequences—it meant punishing them without malice.

Kierkegaard highlighted the scandal of equal love. To love enemies is to resist preference, pride, and retaliation. Bonhoeffer, writing under Nazi rule, took it further: forgiveness is costly grace, but resisting evil is also part of responsibility. He personally joined a plot to stop Hitler—proof that “loving enemies” does not mean passivity.

In the 20th century, Reinhold Niebuhr emphasized the gap between ideals and realities. Agape (selfless love) is the ideal, but in politics we need justice as the proximate tool. C.S. Lewis offered the simplest formula: forgive the sinner in spirit, punish him in practice—for deterrence and reform, not revenge.

Outside Christian thought, the debate is just as rich.

Aristotle saw forgiveness as a virtue balanced between vindictiveness and weakness.

The Stoics counseled forgiveness for the sake of tranquility—don’t let another’s wrongs rule you.

Kant saw forgiveness as a private duty of respect, but insisted the state must punish out of respect for law.

Utilitarians defend forgiveness when it reduces harm, but punish when it prevents greater harm.

Nietzsche was skeptical, arguing that forgiveness often masks weakness.

Hannah Arendt called forgiveness a political necessity: the only way to break the chain of action and reaction that otherwise imprisons us.

Forgive in spirit, punish in practice — every serious thinker ends up there, one way or another.

III. Arguments For and Against

For forgiveness:

It breaks the cycle of revenge.

It frees the victim from corrosive hatred.

It can transform relationships and even societies.

It models virtue and moral courage.

In fragile communities, it may be the only survival strategy.

Against blanket forgiveness:

It can embolden wrongdoers.

It may be exploited by abusers.

It risks treating grave wrongs as trivial.

It may confuse private virtue with public policy.

It runs against human nature in ways that can make it impractical.

The push and pull between these arguments is not a flaw in the tradition—it is the lived struggle of humanity with an ethic that challenges both instinct and circumstance.

Unlimited forgiveness is just a “welcome” mat for repeat offenders — and they’ll wipe their boots on your face.

IV. Modern Application and Tensions

This is where the rubber meets the road. Forgiveness today operates in two very different arenas: personal life and public life.

In personal life, forgiveness can be transformative. Spouses who overcome infidelity, friends who overcome betrayal, families who heal divisions—all testify to the power of forgiveness. It allows people to move on, to grow, and to avoid being consumed by resentment. Without forgiveness, many relationships would collapse under the weight of ordinary human failure.

But in public life, the picture changes. Modern societies rely on deterrence. Corruption, crime, and abuse of power cannot be met with blind mercy. If a public official fabricates charges against political opponents, forgiveness in the personal sense is irrelevant. Justice, deterrence, and protection of the innocent demand real penalties. A republic cannot survive if intelligence chiefs, corporate executives, or war criminals are allowed to apologize and walk away.

This distinction is critical. Forgiveness as an inner release—yes. Forgiveness as public leniency—dangerous. Both may be valuable, but only if carefully distinguished.

The challenge, then, is to avoid two extremes: a society without mercy, where vengeance rules every sphere, and a society without justice, where forgiveness becomes a license for abuse.

If “oops, my bad” were enough, every crook would be canonized before his second trial.

V. A Practical Synthesis

So where does this leave us? A workable ethic balances both imperatives: forgive to free the soul, punish to protect the world.

A. Two-level ethic

Personal sphere: Forgive, release hatred, hope for change. Set boundaries. Reconcile when truth and repentance are real.

Public sphere: Insist on justice, deterrence, and proportional punishment. Mercy follows truth, responsibility, and repair—not denial or repeat offense.

B. The Four-R Test

When facing a wrong, ask:

1. Reality: Has the wrong been truthfully named?

2. Responsibility: Has the offender taken ownership?

3. Repentance: Is there evidence of change?

4. Risk: Will forgiveness or leniency endanger others?

C. Sample language

“I forgive you in spirit, but consequences stand.”

“Mercy comes after truth, not instead of it.”

“I will not carry hatred, but I will press charges.”

This way, forgiveness does not become weakness, and justice does not become vengeance.

Mercy keeps your blood pressure down; justice keeps the wolves from your door. Forget one, and you’re either bitter or dinner.

Conclusion

Forgiveness is not about excusing evil. It is about refusing to be ruled by hatred. Justice is not about cruelty. It is about refusing to be ruled by lawlessness.

Two thousand years ago, forgiveness was the survival ethic of a powerless sect under Rome. Today, it remains a moral challenge—but one that must be joined with justice if we are to survive as free people.

Forgive, so hate doesn’t own you. Punish, so harm doesn’t own the future.

That is the synthesis. That is the why.

I make the distinction because I anticipate a few prominent political bad actors are going to be punished by our legal system. We need to make sure that their punishment is in line with the destruction they caused. No room for pity or misplaced forgiveness in this situation. They should get what they deserve in order to deter future malevolent and dishonest acts. That’s all. Behavior modification, not retribution. But I will believe it when I see it.

Another excellent essay! Revenge and punishment are two different actions.