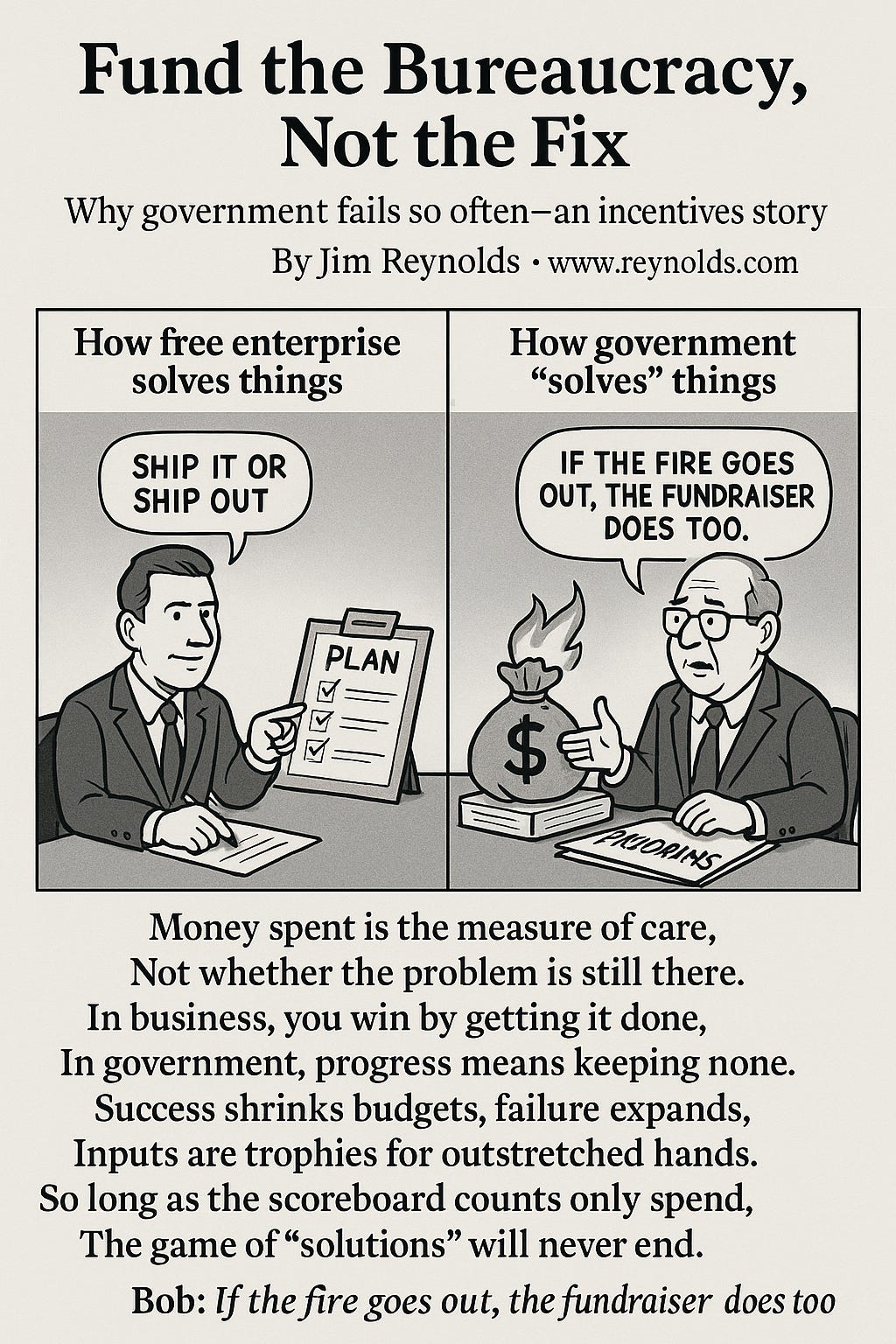

Fund the Bureaucracy, Not the Fix

Why government fails so often—an incentives story

Fund the Bureaucracy, Not the Fix

Why government fails so often—an incentives story

By Jim Reynolds | www.reynolds.com

How free enterprise solves things

A company wants to launch a new product or enter a new market. Step one: decide if the idea is sound, feasible, and timely. Step two: assign ownership—one leader, a small team, clear authority, real resources. Step three: build a plan with milestones, blockers identified, risks priced.

Incentives keep the engine humming: finish under budget and ahead of schedule, you get bonuses, promotions, and bigger scope. Miss repeatedly, and you’re off the team. Result: people are paid to finish—faster, cheaper, better.

Bob: “Ship it or ship out.”

How government “solves” things

The incentives flip upside down. Money is appropriated before a real plan exists. Success, which would require less money, is punished under “use it or lose it.” Headcount equals clout, so offices grow even when problems don’t shrink. Contractors love drift and change orders—they get paid more the longer it drags on.

And when things fail? No consequences. Missed dates become “updated timelines.” Overruns get “supplemental appropriations.” Almost nobody is fired; they’re just “reassigned.”

Result: people are paid to continue—longer, larger, vaguer.

Bob: “If the fire goes out, the fundraiser does too.”

Why incentives diverge

Feedback: Companies face customers and profit/loss weekly; agencies face pressers and appropriations annually.

Risk: Firms take risk to win; officials avoid risk to survive audits and headlines.

Ownership: In business, one name owns the outcome; in government, responsibility is “shared,” which means shed.

Metrics: Firms count profit, time, quality; agencies count spend, staff, and “services delivered” (regardless of effect).

Time horizon: Managers think in product cycles; politicians think in news cycles.

Bob: “When success shrinks your budget, failure has tenure.”

Quick examples (incentives at work)

High-speed rail: Scope shrinks, costs swell, schedule slides. Failure expands the program; success would end it. Incentive: keep digging.

Homelessness: Dollars flow to “contacts,” “beds funded,” and pilots; durable exits are rare. Incentive: serve activity, not outcomes.

Urban schools: Central office grows; proficiency stalls. Incentive: protect the org chart, not the child.

Roads: Big spend, slow fixes. Incentive: manage projects, not finish corridors.

Rent control & permits: Cap prices, throttle supply, then fund subsidies for the shortage you created. Incentive: create recurring need.

Climate theater: Announce goals for 2035, hold summits in 2026, spend trillions in 2027, and measure “success” in slogans. Incentive: push promises past your own career.

Leadership churn: Government projects go on so long that new managers inevitably arrive. Each one brings “adjustments,” which really means starting over. For contractors, it’s a jackpot—every reset means more billable hours, more change orders, more drift.

Bob: “New broom, same dirt—just a bigger budget.”

The Democratic model: Inputs, not results

This is why Democrats never “solve” anything. To them, the scoreboard is not outcomes—it’s inputs. How much money was appropriated? How many contractors were hired? How many programs announced? They measure compassion by dollars spent, not problems fixed.

The results almost don’t matter—because if the problem disappears, so does the budget, the staff, and the political leverage. So problems are managed, not solved. Slogans are updated, not streets. Failure becomes the model, not the accident.

Bob: “In Washington, the fix is in. Just never fixed.”

The scoreboard (six numbers that don’t lie)

On-time delivery rate vs. original schedule.

Variance to budget (actual vs. appropriated).

Cost per outcome, not per “participant.”

Cycle time (permit → completion).

Retention of success (e.g., 12-mo housing exits held).

De-scoping events (how many times the goalposts moved).

If these drift the wrong way while press conferences multiply, you’re not in governance—you’re in guardianship.

Bob: “They fix the narrative, not the problem.”

The bottom line

Free enterprise pays for outcomes. Government pays for activity. One builds better products and services. The other builds bigger bureaucracies. Until the incentives flip, failure isn’t a glitch—it’s the business model.

Grook: Fund the Bureaucracy, Not the Fix

Money spent is the measure of care,

Not whether the problem is still there.

In business, you win by getting it done,

In government, progress means keeping none.

Success shrinks budgets, failure expands,

Inputs are trophies for outstretched hands.

So long as the scoreboard counts only spend,

The game of “solutions” will never end.