Jawboning About Faces, Patterns, and the Trouble with Knowing

The root word is “gnosis”. All understanding starts from there.

Jawboning About Faces, Patterns, and the Trouble with Knowing

By Jim Reynolds | www.reynolds.com

Seven of us cousins—most in our 70s and 80s—gathered at a quiet restaurant the other day. They’d been worried about me for the past year, following my medical journey from afar. Osteoradionecrosis: a nine-syllable monster that sounds like it was cooked up to terrify med students. They wanted the update, straight. So I gave it to them, out loud, no filter.

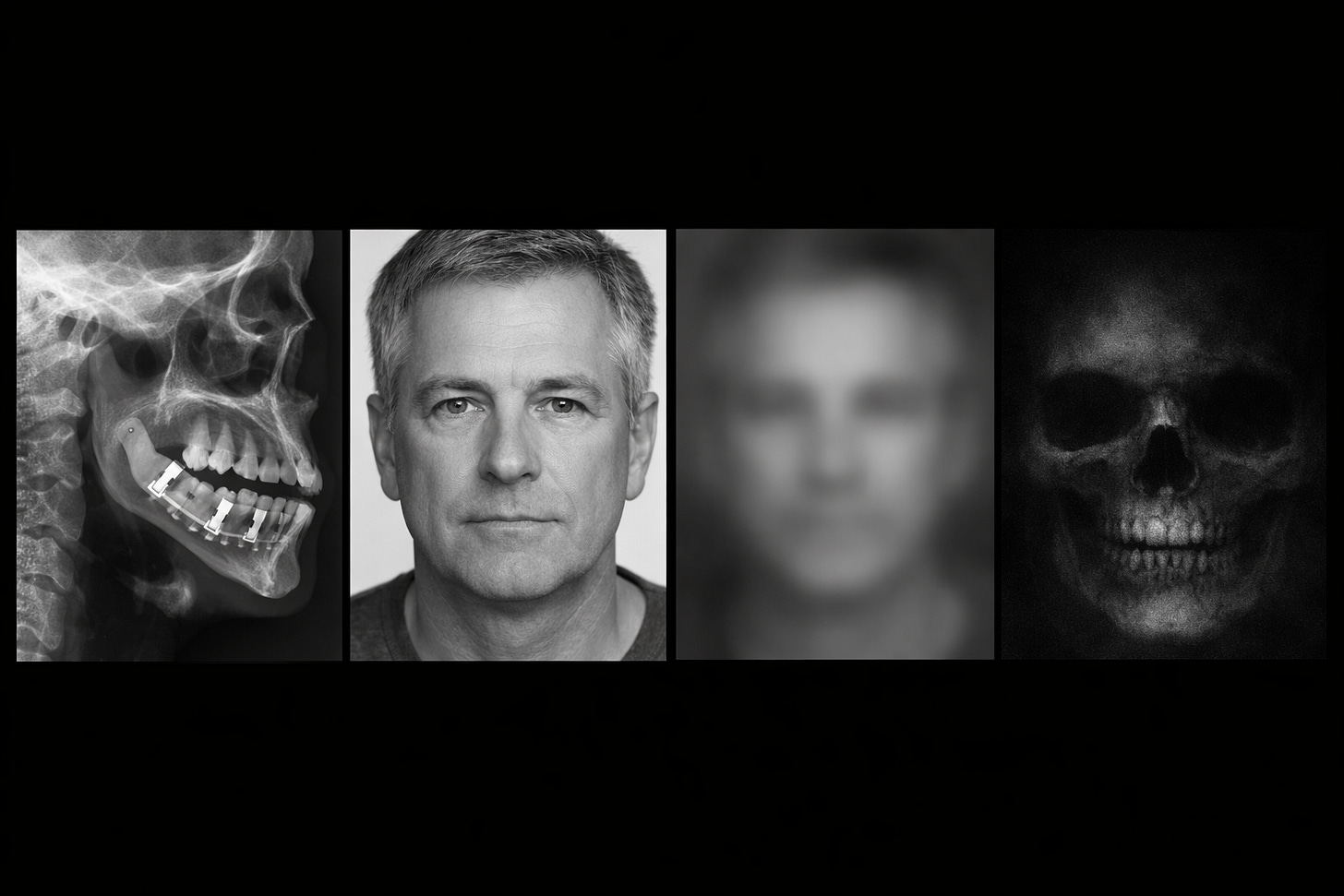

I told them I’m almost normal now. The dead bone in my right jaw is gone, replaced with live bone from my left fibula. A year ago, the oral surgeon sawed out a segment of that leg bone, laid it on the table like a spare part, then screwed two dental implants directly into it. Next, they microsurgically transferred the whole thing—blood supply intact—into my jaw, shaping it to fit, cutting away the necrotic section and wiring it in place.

Yesterday, the surgeon went back in and uncovered those implants, now solidly fused in what used to be my fibula. Final step: head to the dentist for custom crowns to be measured, sized, and screwed on.

Teeth on leg bone. It sounds like science fiction, but it’s just modern reconstructive surgery doing its quiet work.

They listened, wide-eyed. A few jaws dropped—ironic, given the topic. They know I’m the one who tells these stories on the internet, so I leaned into the details. It made a good tale, and it let them see exactly where I stand today: healing, functional, grateful.

The conversation started innocently enough, as these things often do.

Then one cousin, with her nursing background, nodded at my fibula story and said, almost casually, “I finally figured out what I have.”

Prosopagnosia.

Face blindness.

Before I could respond, another cousin’s wife blurted out, “My husband (also present) has that too!”

Then both of them looked at me—politely, blankly—and asked who I was.

That was… unexpected. It may have come from a movie that I imagined to have seen once. Back to the story.

Prosopagnosia affects roughly 2% of the population. Yet here were two people in the same room, discovering it out loud, in real time. They weren’t joking. They weren’t confused. They were relieved. Something finally had a name.

Prosopagnosia isn’t about poor eyesight. It’s not memory loss. It’s a failure of recognition—a failure of knowing-again. Faces don’t resolve into identity. They don’t lock. Everyone is vaguely familiar. Everyone is also a stranger.

Which is fascinating—because I have the opposite problem.

I never forget a face.

I may not remember a name, but I know where I’ve seen someone before. What movie. What show. Who they acted with. Sometimes the year. Sometimes the episode. This drives my wife, Vicki, absolutely nuts.

“Why do you know that?” she’ll ask.

I don’t know. I just do.

It’s pattern recognition. Faces resolve into context automatically. The mind snaps them into place—cognition, in the original sense: the brain’s act of knowing, sorting, and filing what it sees.

Watching my cousins talk about prosopagnosia was like hearing someone describe color blindness while standing in a paint store. They weren’t defective. They were just missing a particular internal mechanism I take for granted.

And here’s where it gets interesting.

Prosopagnosia is a true cognitive limitation. The brain literally cannot perform the task. No amount of effort fixes it. There’s no moral dimension. No ideology. No blame.

But there’s another condition that looks similar from the outside—and is far more common.

Cognitive dissonance.

Unlike face blindness, cognitive dissonance isn’t a failure to recognize a pattern. It’s the refusal to let recognition finish. It’s the mind catching itself—metacognition, thinking about its own thinking—and then using that self-awareness not to correct the error, but to defend the belief.

The evidence lines up.

The pattern repeats.

The outcome is visible.

And yet something in the mind intervenes—not with confusion, but with certainty.

The mind says: That can’t be what I’m seeing.

So it edits. Reframes. Explains away. It runs its own private diagnosis—not “what is true,” but “what explanation lets me keep what I already believe.”

What fascinates me is how calm this process is. People experiencing cognitive dissonance don’t look lost. They look confident. They aren’t unsure—they’re protected.

Prosopagnosia says: I can’t recognize this face.

Cognitive dissonance says: I recognize it—and therefore it must be wrong.

Both are human. Only one is involuntary.

That’s why pattern recognition matters so much. Not politically. Not morally. Cognitively.

Some people can’t recognize faces.

Some people recognize patterns everywhere.

And some recognize patterns—until recognition threatens something they already believe.

That’s where knowing becomes optional.

You see it in politics, in media coverage, in how smart people process inconvenient data.

Gnosis isn’t just seeing. It’s not mere exposure to information. It’s knowledge that lands—recognition allowed to complete its work, without being interrupted by fear, loyalty, pride, or social permission.

And once you notice that difference, you start seeing it everywhere—sometimes even when you wish you wouldn’t.

And now we know a little bit more about how the talented Scott Adams would have framed this phenomenon: one screen, two movies.

Both teams see the same signal.

They just watch entirely different movies.

Prosopagnosia. I had never heard of it before yesterday.

To have two of the seven people at the table realize—out loud—that they had it felt like another coincidence-adjacent moment. But maybe it wasn’t that odd. Those two cousins share something: grandparents. The same ones I have.

Whatever the mechanism, I clearly don’t have face blindness. As I wrote, I have the opposite problem. I remember too much about faces. Even if the context doesn’t snap in immediately, I can usually just sit with the face for a bit. Given time, the background forms. The setting emerges from the mist.

Names, however, are a different story. I almost never remember names.

And I know why.

When I shake someone’s hand, I’m focused entirely on their face—reading it, registering it, looking for clues about how best to interact with this person. The name simply doesn’t make the cut. It never gets encoded.

So there it is. Two different failures. Two different strengths.

Yin and yang, perhaps.

Your jaw procedures are incredible. And cringy. Glad you are doing well.