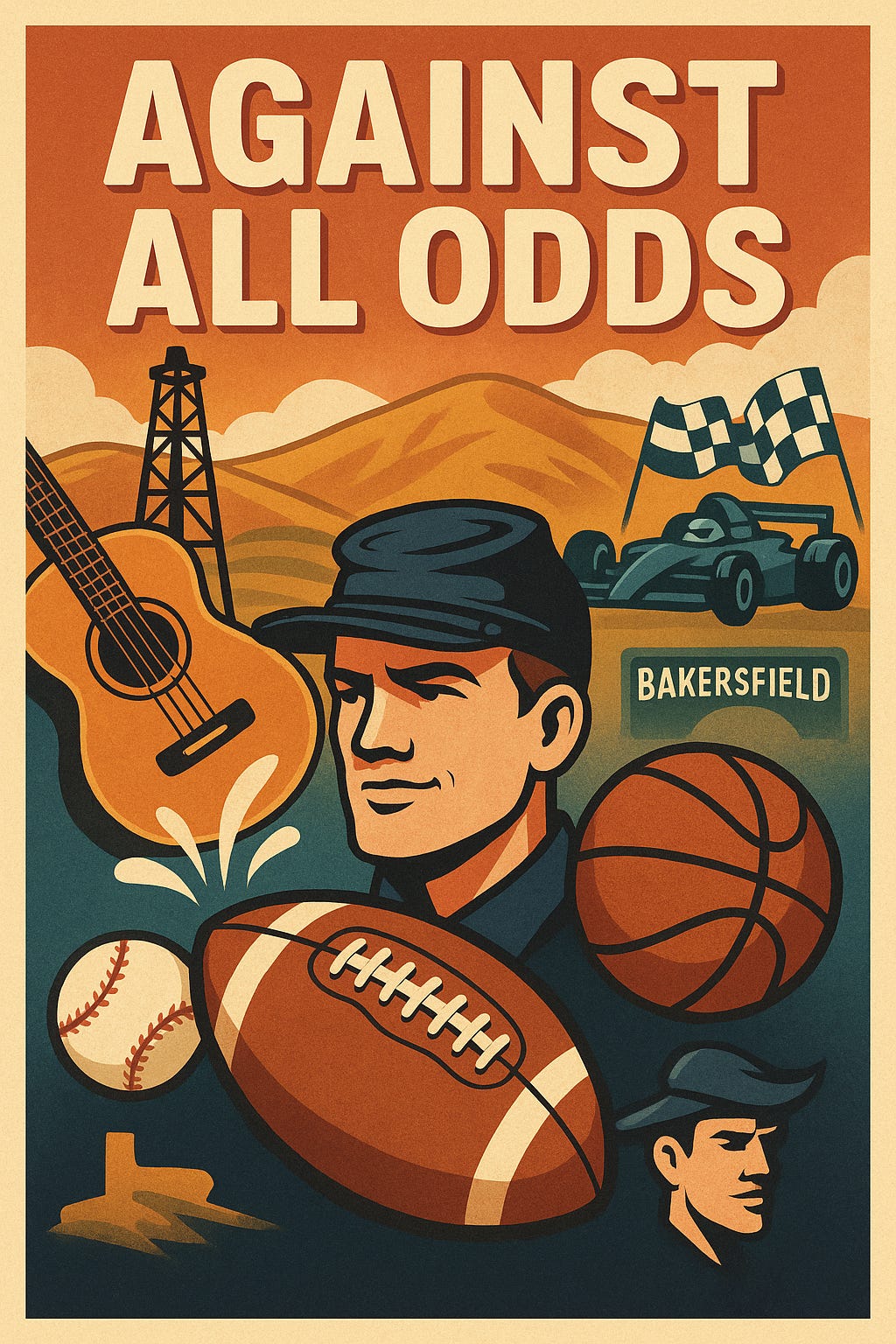

The Bakersfield Five: Against the Odds

How could so much athletic talent come from one place at one time?

The Bakersfield Five: Against the Odds

By Jim Reynolds | www.reynolds.com

Note: This one’s different. It’s not a takedown or a sermon — just a little TGIF story from my hometown in the Valley. Late 1960s Bakersfield wasn’t supposed to be a breeding ground for miracles, unless you count Buck Owens at the Blackboard or Merle Haggard singing at Trout’s. And yet, somehow, an incredible wave of athletic talent rose all at once and spectacularly broke the odds. Not just in one sport, but across football, basketball, baseball — and even racing.

I wasn’t one of the Big Five, but I was right in the middle of it — close enough to hand off, get hit, back up, and even outscore greatness now and then. This isn’t really about athletic feats; it’s about a small, dusty farm town shrugging off the math and saying: “Sure. Why not us?”

Every high school athlete dreams about the next level. The truth is, almost none get there—or stay. Out of more than a million boys who suit up for high-school football in a given year, only about 1 in 4,000 will last three or more seasons in the NFL. In basketball it’s closer to 1 in 18,000 for the NBA; in baseball, around 1 in 5,000 for MLB. The funnel is brutal.

By those odds, a single graduating class might expect zero long-tenure pros—maybe one across several years if a town gets lucky. Yet in late-1960s Bakersfield, I crossed paths with five who beat the funnel, across three different sports. I didn’t just hear their names—I handed off to them, got hit by them, guarded them, backed them up, and knocked them out of bounds.

Below are those snapshots—up close, before the headlines.

Junior Kennedy

I first met Junior in junior high on a track: he won a middle-distance race; I finished second. That was Junior—an all-around athlete at Arvin: football, basketball, baseball. Not oversized, just pure athlete. Arvin is a farm town just south of Bakersfield.

Years later under the lights, South was down 25–0 at Arvin when Junior broke loose down the sideline. I was playing safety. I caught him at full speed, hit him high, and knocked him out of bounds. He was hurt—leg or shoulder, I can’t remember—and he wasn’t quite himself in the later championship games. I never took pride in that. It happens in football, but standing there in front of a hostile crowd, I half-expected folks to come out of the bleachers after me.

Junior went on to play nine MLB seasons for the Reds and Cubs, a versatile infielder in the Big Red Machine era.

Brent McClanahan

Brent was a year behind me at South. He started at quarterback for a couple of games until everyone realized passing wasn’t his gift. What he did have was balance, explosive power, and a determined running style. I moved to QB1, and most of my offensive memories that season are handing Brent the ball and sending him off-tackle right behind our fullback and our only reliable O-line blockers.

We seniors quickly found ourselves living the dreaded “building year”. Not much fun for seniors—but it worked. The next season, South won the Valley championship. Brent went on to Arizona State and then seven years with the Vikings, appearing in three Super Bowls.

(And yes—I was the faster runner.)

Jeff Siemon

Bakersfield High was the local powerhouse, and Jeff was their middle linebacker—already playing like a future first-rounder. Our center weighed maybe 160 pounds. Jeff lined up four feet away, eyes on me. If I even thought about throwing, he was in the backfield before I could set my feet. It wasn’t fair, but it was real.

BHS flooded our off-tackle lanes and shut Brent down. We switched to a frantic run-and-throw offense that stole a few yards but couldn’t sustain drives. I’m pretty sure Jeff picked off one of my passes that night.

He later became the 10th overall pick in the 1972 NFL draft, four-time Pro Bowler, defensive captain, and a rock through three Vikings Super Bowl runs.

Dave Rader

Dave was almost my next-door neighbor; his brother Bob was my classmate and friend. By his sophomore year everybody knew Dave had big-league potential. Then, senior year, he surprised us—he took the quarterback job. He wasn’t a natural passer, but he had presence and fundamental athletic ability. The team trusted him, and we were a ground-heavy offense anyway.

I was the junior understudy—the “Hail Mary” guy when games tilted the wrong way. Everyone knew Dave’s true lane was baseball. He proved it: first-round pick of the Giants, ten MLB seasons, a steady defensive catcher with real staying power.

Freddie Boyd

Freddie Boyd was the best natural athlete I ever played against. He started on East High’s varsity basketball team as a freshman and could have led the league in scoring every year if his team hadn’t been loaded. He wasn’t the purest shooter; he didn’t need to be. He was quicker, stronger, and more agile than everyone else on the floor. If he wanted to score, he scored.

He concentrated on basketball, and East rattled off three or four straight titles with him at the core. I did have one personal win: in his last regular-season high-school game, I outscored him. To be fair, he had a broken finger that night—but it’s in the books.

Freddie went to Oregon State, became the #5 pick in the 1972 NBA Draft, made the All-Rookie Team, and played six NBA seasons.

The Improbability of It All

Remember the funnel:

Football: ~1 in 4,000 HS players last 3+ NFL seasons

Basketball: ~1 in 18,000 last 3+ NBA seasons

Baseball: ~1 in 5,000 last 3+ MLB seasons

Even in a sports-crazy town, the chance that one small circle yields five long-tenure pros is vanishingly small. Spread those five across all three major sports—not clustered in one pipeline—and the odds get freakish. It’s not just “less than one in a million.” It’s closer to one in a billion, unless you believe in talent clustering, golden generations, and a little hometown magic.

I wasn’t one of the five. My road led to music, teaching, and software. But I carried those nights and names with me. They’re proof that greatness can appear anywhere, in any era—sometimes all at once.

In my case:

Greatness was right across the line of scrimmage.

Greatness was running down the sideline.

Greatness was ahead of me in the QB depth chart.

Greatness was waiting for my hand-off.

Greatness was displaying the finest high school basketball talent I ever saw.

Bottom line: the math said this time-synchronized combination of talent and work ethic should never happen.

Bakersfield said: “Hold my Coors. Watch this.”

Note: If you think everything I’ve just described was impossible — and statistically, it was — then read on. Because Bakersfield wasn’t finished. The story doesn’t end with the Five. What came next only makes the odds even crazier.

Bonus Feature: Steve Ontiveros

Steve Ontiveros was one year behind me at Bakersfield High. Unlike Brent, Jeff, Dave, Junior, and Freddie, I don’t recall sharing the same field or court with him. But we were of the same era, and his career adds another remarkable thread to Bakersfield’s tapestry.

In a unique way, his baseball career was even more accomplished than those presented above. You’ll see why.

Steve logged eight solid seasons in the majors with the Giants and Cubs, batting .274 with more than 600 hits while anchoring third base. His best year came in 1977, when he hit just shy of .300 and played nearly every game for Chicago.

Then, when most players would have been winding down, Steve made history: he signed the first million-dollar contract in Japanese baseball with the Seibu Lions. He didn’t just extend his career—he thrived, hitting .312 with 82 home runs and nearly 400 RBIs over six seasons in Japan.

Steve didn’t just play professional baseball; he helped change it, opening a door between American and Japanese leagues that others would later walk through.

His story adds yet another longshot—another 1-in-5,000 climb to the pros—stacked onto the already impossible odds of so much sports greatness emanating from one place, at one time. Bakersfield’s reach, it turned out, stretched even farther than we imagined.

Bob: “And you thought ’60s Bakersfield was just about Buck Owens and Merle Haggard!”

Second Bonus Feature: John Tarver

John Tarver was born in Bakersfield, one of nine kids in a family that seemed built to produce athletes. He first made his mark at Arvin High, then at Bakersfield College, before heading to Colorado, where he piled up 1,327 rushing yards and appeared in three bowls, including the Liberty and Bluebonnet.

In high school he was a standout three-sport star, as were his siblings at Arvin. He was in the high school class before mine, playing alongside Kennedy.

Drafted by the Patriots in the 7th round of 1972, Tarver spent three seasons in New England before finishing with the Eagles in 1975. In 1973, he was the Patriots’ second-leading rusher — despite missing five games.

Tarver didn’t just carve out his own career; he left a legacy. His son Shon later played basketball at UCLA, and another son, Seth, suited up for the Idaho Stampede.

Bakersfield hadn’t just produced one NFL running back in Brent McClanahan — it produced two. I played on the same team with one, and tried to tackle the other. At 6’3” and over 220 pounds, John Tarver was a nightmare to bring down without help.

John represents one more impossible odds-breaker: only 1 in 4000 high school senior football players achieve a 3+ years career in the NFL.

Final Surprise Bonus Feature: Rick Mears

Rick Mears graduated from South High in 1970, just two years behind me. While I was under center handing off to Brent McClanahan, Rick was busy in the garages and dirt tracks, teaching himself the feel of speed and the discipline of control. Nobody at the time could have guessed that this quiet kid from Bakersfield would become one of the greatest racecar drivers in history.

But that’s exactly what happened. Over the next two decades he became the face of Team Penske, winning the Indianapolis 500 four times (1979, 1984, 1988, 1991), tying the all-time record. He set the record for six Indy poles, and added three CART championships to his name. Mears was revered not just for victories but for his calm, calculated style — the man who could dice through a pack at 220 mph without ever seeming rattled.

So add Rick to the roll call. Another South High product. Another career that should have been statistically impossible, but somehow wasn’t.

How does this happen? How does one small, dusty town in California — in the span of just a few years — produce not only pros in the NFL, NBA, and MLB, but one of the greatest racecar drivers who ever lived? Bakersfield shouldn’t have had those odds. But it did. And I was there to see it.

And the whole time, the Bakersfield Sound was just warming up at Trouts and the Blackboard, just across the Kern River in Oildale.