The Landslide They Couldn't Forgive

How Nixon's 1972 Victory Made Him a Mark

The Landslide They Couldn't Forgive

How Nixon's 1972 Victory Made Him a Mark

Slogans that Framed a Presidency

Nixon’s 1968 campaign ran under the banner of “Nixon’s the One”—a message of steady leadership in a time of chaos. By 1972, his reelection slogan was even more confident: “Now More Than Ever.” Together, they told a story of redemption, order, and strength—and the country responded.

I. The Setup: Nixon’s 1968 Win and a Nation in Turmoil

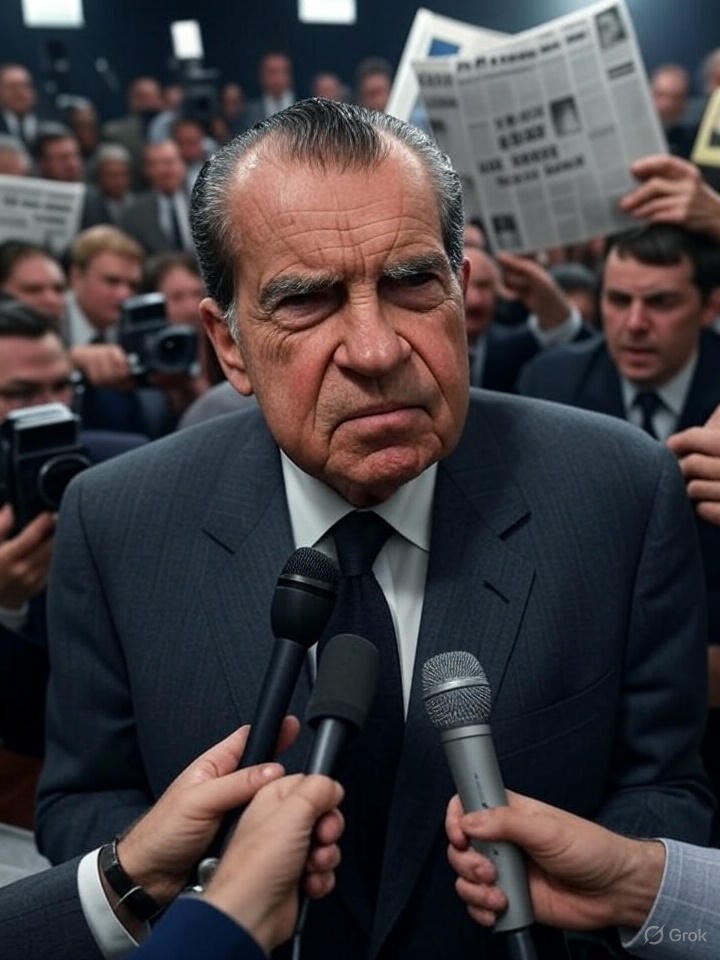

Richard Nixon returned from political exile in 1968 with a simple promise: end the war in Vietnam and restore order at home. After years of Democratic escalation abroad and chaos on the streets—riots, assassinations, the 1968 Democratic National Convention—voters turned to Nixon not with love, but with a sense of necessity. He promised peace with honor. He spoke for the Silent Majority. He won narrowly, but the mandate was clear: fix what the Democrats had broken.

II. The Hogtie: How Democrats Sabotaged His First Term

Nixon began troop withdrawals and negotiated with North Vietnam, but the Democratic Congress undermined his efforts. Anti-war Democrats withheld funding and support, forcing Nixon to navigate peace through a minefield of domestic sabotage. Meanwhile, the media painted him as a paranoid authoritarian.

The campus unrest exploded. From Kent State to Columbia to UCSB, students shut down universities, stormed administration buildings, occupied student unions, and brought in riot police. Tear gas became a fixture. Final exams were canceled. The country watched in horror as militant radicals became the face of higher education. Reagan, then governor of California, didn’t hesitate to rattle his saber, winning cheers from a rattled public. This wasn't protest—it was insurrection in miniature, and the center of the country was furious. They blamed the Democrats.

Jim: I was a 20-year-old conservative student at UCSB in 1970. Even then I felt like part of an underrepresented minority on campus. UCSB and adjoining Isla Vista erupted in campus riots that spring. A half block away from our apartment, they burned the Bank of America down. Riot control officers were shipped in to sweep the streets with a phalanx of armed and helmeted police. Tear gas was in the air for most of the night. Eventually, the inevitable happened: Kevin Moran, a graduate student and peace maker, was accidentally shot dead outside the temporary BofA structure. It doesn’t get much more serious than that. I was there, wondering why the lefties (very few actual students) were doing what they were doing.

III. 1972: The Blowout Nobody Wanted

By the time 1972 arrived, Nixon had achieved the unthinkable: troop levels in Vietnam were down dramatically, the draft was winding down, and peace negotiations were real. The economy was steady. The opposition was weak. McGovern was radical, inexperienced, and burdened with campaign chaos, including the Eagleton VP debacle.

Polls throughout the summer and fall showed Nixon with a commanding lead—often double digits. Some outlets grudgingly endorsed him, not because they supported him, but because it was clear he was going to win. But they predicted a 10–12 point win, not a generational landslide.

IV. The Reality: 49 States and a 23-Point Margin

When the votes were counted, Nixon didn’t just win—he obliterated. Over 60% of the vote. 520 electoral votes. 49 states. The largest popular vote margin in modern American history. Even traditionally liberal states fell into his column. The Silent Majority didn’t whisper—they roared.

And that roar humiliated the media. They had underestimated him. Again. Their reluctant endorsements now looked like too little, too late. And it wasn’t just Nixon who won. The media lost. Their grip on the national mood was shattered.

V. The Turn: From Reluctant Endorsement to Relentless Destruction

They couldn't take it. The same media class that had gritted its teeth to acknowledge Nixon's inevitability in October of 1972 turned on him with a fury by early 1973. Every mistake, every misstep, was magnified. Watergate, which had simmered quietly during the election, suddenly became the hammer they needed.

Make no mistake: Nixon's actual misconduct mattered. But so did the vengeance. He had embarrassed them. Outsmarted them. Outmaneuvered their candidate, their narrative, and their cultural grip. And for that, they needed him gone.

VI. The Media’s Guilt and Revenge

The media’s about-face wasn’t driven solely by principle. It was atonement. They had endorsed the man who humiliated them. They had misread the public—again. And rather than ask why, rather than reflect on their own isolation from middle America, they made Nixon the scapegoat for everything wrong with the country.

This wasn’t justice. It was penance.

VII. The Precedent: When Winning Big Becomes a Crime

Nixon’s landslide didn’t protect him—it doomed him. He didn’t just beat the Democrats; he shattered their moral superiority. And in doing so, he provoked a vendetta that culminated not just in his resignation, but in a new media doctrine: never again allow a populist outsider to claim that kind of power.

That doctrine has lived on—in their treatment of Reagan, of Trump, of anyone who threatens their status.

VIII. Backdrop: Who Was the Media?

To understand the full scope of the backlash, consider who controlled the public narrative. The New York Times. The Washington Post. The Associated Press. United Press International. CBS, NBC, and ABC. The Chicago Tribune and Sun-Times. These weren’t just newspapers and broadcasters—they were gatekeepers.

They claimed objectivity but leaned left. There was no Fox News. No talk radio. No internet. No Substack. The so-called mainstream media was the only stream, and it flowed in one direction: liberal, institutional, and increasingly antagonistic toward Nixon's brand of conservatism.

These outlets spoke the language of centrism while pushing narratives shaped by urban, anti-war, anti-Nixon sentiment. They mocked the Silent Majority and minimized the cultural rift between elites and middle America. When Nixon crushed McGovern, they weren’t just shocked—they were exposed.

Even comedy wasn’t neutral. The Smothers Brothers, popular for their variety show on CBS, used satire to hammer Nixon and the war—until the network fired them in 1969 for going too far. Their ousting only burnished their anti-establishment credibility, and they became symbols of Hollywood’s turn against Nixon-era conservatism. It was unprecedented at the time for a network variety show to target a sitting president so openly—marking an early sign of prime-time propaganda dressed as humor. What began as counterculture critique would soon become institutional norm.

IX. Lone Voices in the Wind

At the time, conservative voices in media were scarce—but not nonexistent. In Chicago, columnist Mike Royko—though often centrist-populist rather than hard-right—occasionally broke with liberal orthodoxy and captured the frustrations of working-class Democrats. In Los Angeles, George Putnam delivered right-leaning commentary on local television, becoming an early broadcast voice for traditional American values. And William F. Buckley, through National Review and his TV show Firing Line, upheld intellectual conservatism, though often in tones too rarefied to reach Nixon’s blue-collar base.

Also worth noting: early commentary from Pat Buchanan, a young speechwriter and aide to Nixon, helped sharpen the ideological contrast behind the scenes. But in the mainstream, these voices were isolated. The press corps in D.C. was overwhelmingly liberal, and newsrooms across the country often functioned as echo chambers.

The dominant media landscape leaned left—not in open declaration, but in default assumption. To be “mainstream” meant being skeptical of Nixon, sympathetic to anti-war demonstrators, and comfortably removed from the anxieties of middle America. The few dissenters were either sidelined or patronized, treated as oddities in a monologue culture that mistook itself for dialogue.

X. End Note: The Win They Couldn't Forgive

In the end, Nixon's real crime wasn't Watergate.

It was winning.

Too big. Too loud. Too confidently. And forcing the media to face a country they no longer understood.

They never forgave him for it.

GROOK: The Story They Needed

in the style of Piet Hein

The tale was small, the truth was thin,

But thick enough to hang him in.

For once they taste a hero's fall,

The press forgets the crime was small.