The Price of Perk: A Short, Strong History of American Coffee

Was Dr Crane part of the marketing strategy?

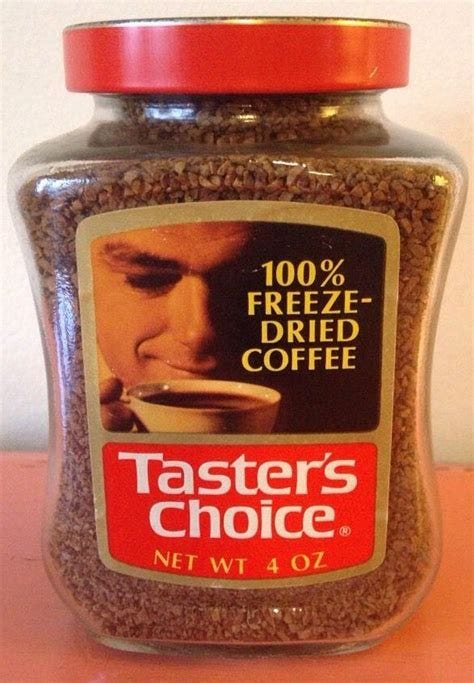

The original Taster’s Choice jar, circa early 1970s. Our “Taster” didn’t need latte art or Wi-Fi — just hot water and faith in freeze-drying. What it lacked in aroma it made up for in convenience.

The Price of Perk: A Short, Strong History of American Coffee

By Jim Reynolds | www.reynolds.com

Every morning, America performs the same ritual. We grind, pour, or press. We push buttons, wait for drips, and call it productivity. But few stop to ask: what are we really paying for — and when did our morning habit turn into a financial statement?

The Daily Transaction

Coffee has become our smallest and most loyal tax. Whether it’s beans, pods, or paper cups, someone is making a margin off your caffeine. The difference between a fifty-cent mug and a six-dollar latte isn’t chemistry; it’s psychology. Every cup is an exchange between time, taste, and self-image.

The Instant Revolution

Long before Starbucks taught America to speak Italian, a simpler revolution had already taken place. Sanka arrived in the 1920s, selling calm in a cup. Then, in 1967, Nestlé launched Taster’s Choice — that glass jar with the debonair “Taster” on the label. He looked like he’d sampled the beans himself, nodded solemnly, and approved your life choices. For singles, students, and travelers, freeze-dried coffee was liberation in a jar. No machine, no filter, no cleanup. Just hot water, a spoon, and independence. What it lacked in aroma it made up for in convenience. If you were living alone in the early ’70s, that jar was your roommate. It wasn’t fancy, but it worked. It was modernity without maintenance — the democratic brew.

The Jingle Years

There was a time when coffee didn’t whisper lifestyle—it sang. Folgers was “Mountain Grown—In the Flavor Zone.” You were told to “Head for the Hills” with Hills Brothers. Maxwell House was “Good to the last drop.” Johnny Carson sold Yuban on live TV, smirking like he’d already had three cups. Even Sanka, the underdog of the decaf world, told you to “Love coffee again.”

Those ads weren’t just selling flavor; they sold goodness. Coffee was relational. A husband poured it for his wife before work. A neighbor brought it to your porch. A hostess refilled your cup as a sign of warmth and regard. Brewing coffee was a small act of devotion — proof that kindness didn’t need ceremony.

And the scoreboard told the same story. In 1964, America’s top regular coffee brands looked like this: Maxwell House 21%, Folgers 15%, A&P 12%, Chase & Sanborn 8%, Hills Bros 7%, Duncan’s 5%, Yuban 1%. Seven names, all familiar, all sitting in the grocery aisle — not behind a counter with Wi-Fi. They didn’t need influencers, hashtags, or secret menus. They just needed to smell good.

The jingles faded not because the product failed, but because the culture changed. When Starbucks arrived, coffee stopped needing to sing. It became a badge. You no longer woke up to a chorus — you stood in line and recited your order.

The Great Complication

By the 1980s, the percolator gave way to Mr. Coffee and the countertop arms race began. Every new machine promised a better brew. Then came the café boom. Starbucks, Peet’s, and Caribou turned caffeine into identity. Foam replaced flavor. Renting a table became a lifestyle. We learned Italian nouns to order what used to be called “coffee.” The patron saint of this foam-forward effeteness was, of course, Dr. Niles Crane — who would dependably rattle off a multisyllabic concoction to the weary barista and call it breakfast. Coffee stopped being communal and became performative. A cup no longer said “wake up.” It said “notice me.”

Little-known fact: the first outfit to sell specialty coffee in a dedicated space in Seattle wasn’t Starbucks — it was Nordstrom. I was there. The same store that sold dress shoes and cologne was also selling lattes before the green mermaid ever swam ashore. Even then, coffee was becoming couture.

The Pod Empire

Enter Keurig, the industrialization of convenience. The pod was sold as freedom — one push, one cup, one planet’s worth of plastic. You could technically use a pod twice, but the second brew tastes like regret. The grounds are engineered for a single extraction. The value disappears the moment you try to stretch it. It’s economics disguised as engineering: sell you the machine cheap, then rent your mornings back to you one pod at a time. The system rewards waste because it guarantees dependence — capitalism’s cleanest loop.

The Cost of the Cup

Let’s pull the curtain back on the economics. Assume one and a half cups a day — about 548 a year. The caffeine’s the same; only the price of illusion changes.

A year of coffee looks like this:

• Freeze-dried instant (Sanka, Taster’s Choice): about $0.32 a cup — $175 a year.

• Brew your own (drip or stovetop): around $0.48 a cup — $263 a year.

• Motel-style pouch: roughly $0.90 a cup — $493 a year.

• Keurig pod: about $0.95 a cup — $521 a year.

And now, going outside the home:

• Diner drip: $2.75 a cup — $1,507 a year.

• Starbucks drip or Americano: $3.75 a cup — $2,055 a year.

• Starbucks latte or cappuccino: $6.25 a cup — $3,425 a year.

Same caffeine molecule, seven price points. The difference is story, packaging, and self-delusion.

The Price of Pretend

We tell ourselves it’s just coffee, but it’s also a confession. It reveals what we value: control, convenience, or company. Brew it yourself and you’re a realist. Buy it daily and you’re a believer — in branding, routine, and the myth of affordable luxury. $200 a year or $3,000 — same bean, different faith. One buys clarity, the other buys comfort. Both have caffeine, but only one has conscience.

The Honest Cup

Coffee used to wake us up. Maybe it still can — if we make it ourselves. It’s the perfect mirror of modern economics: cheap to make, expensive to perform. The truest taste of freedom isn’t found in foam; it’s in the quiet hiss of your own kettle, the steam rising from a mug you brewed yourself. No markup, no middleman, no packaging, no marketing department — just heat, water, and willpower. The difference isn’t mercy. It’s markup. And the first step toward waking up is honesty.

Good to the last drop.

One of your recent best.